Electroconvulsive Therapy was first introduced as a treatment for mental illness in 1938. Today, its main use is in severe treatment resistant depression, as well as in catatonia and the depressive phases of bipolar affective disorder.

The most recent statistics for the UK indicate that over 1,800 patients received courses of ECT during the year 2021. The average number of treatments per course was around 10.

The perception of ECT as a treatment was not helped by its depiction in the Jack Nicholson film One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, but in reality it is a lot safer than most antidepressant medication.

The mortality rate for ECT treatment is 0.002% that is, the chances of dying as a direct result of receiving ECT are only 1 in 100,000. When compared to the suicide risk for people with severe depression, that seems like good odds, if it works. ECT even compares well to mortality rates for antidepressant medication.

In the past, patients were given vast amounts of ECT. I once worked with a woman with a very long history of bipolar affective disorder, who was incarcerated in an old-style asylum for 10 years during the 1960’s. She reports that she received several hundred ECT treatments, and I have no reason to doubt her. However, according to the most recent figures, the average number of treatments per course is only 10.

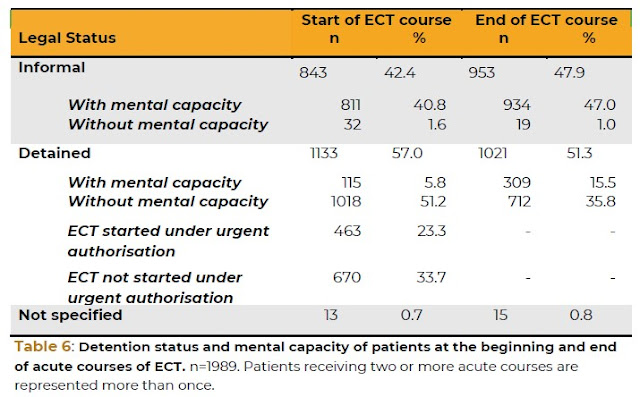

Because of its controversial nature, the whole issue of ECT has a special place in the Mental Health Act. One of the amendments to the Act in 2007 was the addition of s.58A. This section applies to detained patients and to all patients aged under 18, whether or not they are detained. ECT cannot be given to a detained patient unless they consent and are deemed to have the capacity to consent. Equally importantly, ECT cannot be given to a patient lacking in capacity who has made a valid advance decision to refuse ECT.

There are, however, still circumstances in which patients can receive ECT even though they lack the capacity to consent, or when they do have capacity and have refused. This is where a SOAD (a Second Opinion Approved Doctor) certifies that the patient lacks capacity to consent and considers that the treatment is appropriate, there is no advance decision refusing treatment, no one with power of attorney objects, and there is no conflict with any Court of Protection decisions.

This means that ECT can only be given if an independent, specially approved psychiatrist has looked at the individual’s case and has authorised it.

In the case of a person who does have capacity, but has refused to have this treatment, the only circumstances in which ECT can still be given are when treatment with ECT is immediately necessary to save the patient’s life, or will prevent a serious deterioration of their condition or will alleviate serious suffering by the patient”, or will prevent the patient from behaving violently or being a danger to himself or to others.

Important Note: If you are a service user (or potential service user) who objects to the idea of ECT, but thinks it’s possible you might be given ECT at some future time, it is important to make an advance decision now (under the Mental Capacity Act) stating clearly what your wishes for treatment are. Ideally, you should get a solicitor to draw up this document to ensure that it is legally sound.

There are two main situations in which the issue of ECT is likely to arise in a professional context for AMHP’s.

The first is when an AMHP is asked to make an application under Sec.3 for treatment for the specific purpose of giving them emergency ECT. This can present an AMHP with a dilemma: should the MHA be used to compel a treatment which the Act itself regards as being of a different order from other treatments for mental illness, to the extent that it was amended specifically to reflect the unease with which many people regard ECT?

Whatever the personal view of an AMHP regarding the use of ECT, an AMHP must remember that their role is only to make a decision regarding whether, in all the circumstances of the case, a person needs to be detained under the Act in order to receive treatment; it is not their role to decide what form that treatment should take.

The other occasion in which an AMHP may become involved is for consultation under Sec.58A(6). The SOAD, before certifying that a patient should have ECT but is lacking in capacity, must consult with two other professionals who have been involved with the patient’s treatment; while one of these has to be a nurse, the other must be “neither a nurse nor a registered medical practitioner”. An AMHP who has assessed the person could therefore be the second consultee.

For more information on ECT statistics, take a look at this excellent blog, the title of which says it all.

For a positive account of ECT, take a look at this Guardian article.

No comments:

Post a Comment